By Cathy Paveley What is a costume? The Miriam Webster dictionary defines it as:

· the prevailing fashion in coiffure, jewelry, and apparel of a period, country, or class

· an outfit worn to create the appearance characteristic of a particular period, person, place, or thing

· a person's ensemble of outer garments

What do we think of when we talk about Middle Eastern/Sharqi (belly dance) performance costumes? Probably not ‘prevailing fashion’ of a country or class. Yet fashion is involved.

How about ‘apparel of a period or country’? No doubt we think of our dance costumes as somehow representative of the nebulous middle east, even though they are only for performance art.

What about class? This is a little harder to pin down. Do ME dancers belong to a certain class? In the middle east they sometimes do, and this is true here in the west as well. Has that impacted our costumes? Maybe.

Do we wear our costumes to create the appearance of a particular person? Here in the west, we try to create the look of what we think is an Arabic dance artist. Where do these ideas come from and what is their origin? I think we have to go to the third bullet: a person’s ensemble of outer garments.

Before 1900

Before the industrial revolution, fabrics were made by hand, expensive, and hard to come by, unless you were wealthy. Ordinary people had fewer clothes, kept them longer, and couldn’t afford to consider fashion. Performing artists wore their own clothes and decorated them by whatever means available. Today, when we look at illustrations of dancers from the 1800s, we are seeing clothing of the time and place, and not special costumes. When we make a Ghawazi coat or Turkish şalvar (baggy pants) or Lebanese tantour (headpiece) we are re-creating the style of the day, not the costume of the day.

Up until this time there were few professional dancers in the middle east. Although social dancing was common in certain countries, it was usually segregated by gender. In Egypt professional dancers were sometimes invited to perform at weddings and other special occasions (the Hagallah for example), but there is no historical data to indicate what they wore.

Then, in the early 1800s, perhaps earlier, roaming dancers began to appear in some urban areas of Egypt. They were the Ghawazi.

These dancers performed on the street, in small venues, and at special occasions. Their style was influenced by rural traditions of upper Egypt (Saidi), often dancing with sticks and swords. They wore traditional clothes of the time, the styles of which had been greatly influenced by Turkey; vests or boleros, wide pants, long coats, and sometimes a scarf tied around the hips. Eventually the Ghawazi were banned from Cairo, supposedly because of their colourful and sexually suggestive clothing, but research has shown that it had more to do with their refusal to pay city taxes.

In the later part of the 19th century the Awalem appeared. They not only danced, but sang as well, and sometimes recited poetry and told stories. Awalem performed in houses and other private venues, and may have been the first entertainers to wear costumes as we think of them today.

A sidenote – in those days, women who had to support themselves had few opportunities, and since prostitution was legal in Egypt in the 1800s, combining singing, dancing, and prostitution was a viable and somewhat safe practise. This had an influence on what they wore; needing to draw attention to themselves and enhance their movements (or conversely, needing to draw attention away from mediocre abilities).

1920s

This all changed with the arrival of Badia Masabni in the 1920s.

Badia began her career as a singer in a French cabaret in Beirut, Lebanon. Later she moved to Cairo and opened up cabaret of her own, eventually establishing a dance school, and revolutionizing the way dancers performed in public.

In 1926, she originated the concept of the nightclub in the middle east where both men and women could be in attendance. Influenced by Western music and entertainment, she intruded new instruments such as cello, violin, and accordion (the last two forever becoming part of Arabic dance music).

By this time, the Middle East had become popular with European tourists. In order to satisfy westerners, she started introducing classical dance movements. All of these factors resulted in new dance styles, and costumes had to keep up. Colour and glitter were added

for stage effect.

Two-piece costumes showing a bare midriff, veils, head pieces and gauntlets were introduced. Dancers started wearing high heels or other hard dance shoes. The violin and accordion inspired softer, slow movements that were enhanced by flowing skirts. Badia’s influence was felt all over the middle east. Suddenly being a dancer was a viable career, requiring skill and training, although still not widely accepted by the upper classes.

Many dance artists were trained at Badia’s school and went on to perform in her cabaret, including Taheyya Karioka, Samia Gamal, and Niama Akef.

This period became knows as the Golden Era, and this is when costuming took off.

Golden Era (1930s to 1950s)

From here the dance scene moved into what is referred to as the Golden Era. At this time, costume styles took on a very modern look which is still the basis for most styles today.

Dancers were now being featured in Egyptian movies, and their elaborate costumes influenced what performers wore in nightclubs.

Skirts were flowy and semi-transparent. Glittery bands tied around the waist to show off hip movements were very popular. These made a come-back in the 80s and again in the 2010s, interestingly enough. If something is old enough it’s always new again. Puffy sleeves can bee seen in movies of this time.

Toward the end of the 1950s, high heels became less popular in Egypt, possibly influenced by National folkloric troupes like Reda and Kaoumiya. However, they remained popular in Lebanon and Turkey.

Taheyya Cariocha, Samia Gamal, and Naima Akef

The end of the golden era was heralded by Gamel Abdel Naser, who was elected President of Egypt in 1956, four years after the revolution. Under his watch, Egypt experienced what might be called a golden age of culture; film, television, and theatre, but, alas, not belly dancing. Both the Reda Troupe and the Kaoumiya were established, and they endeavoured to bring legitimacy to Raqs Sharqi. Nasser’s control of Egypt was absolute; he began keeping tabs on everyone who had public influence. Badia Masabni was one of those people, and after being harassed by the authorities she sold her nightclub and moved back to Lebanon. Taheyya Karioka, on the other hand, was imprisoned.

Severe restrictions were put on dance costumes and this led to the introduction/imposition of the body stocking. It became illegal to perform with a bare midriff, but artists and costume makers did not let this rule hold them back. The body stocking became very stylish and was adopted by dancers in other countries, just to follow trends.

1960s and 1970s

While costume restrictions were still in place, Nagua Fouad began performing. Her shows became big extravaganzas, with choreographies and costume changes. She showed lots of leg, wearing skirts with wide front slits, and these became the new fashion. Nagua was innovative and often danced with feathers or large fans.

After the Golden Era, dancers often wore stylized Baladi dresses with low fronts to

accommodate beaded bras. They covered the body and allowed dancers to more folk style movements. When Fifi Abdo once appeared in a traditional white men’s gallabiyah it became all the rage. Fifi pushed other boundaries as well, such as appearing in public smoking an Argileh (water pipe), something only men did.

Other Countries

Lebanon and turkey did not have the same political or cultural restrictions as Egypt. Nightclubs and professional dancers proliferated. They toured Europe and North America where belly dancing became a hit. Western performers had their own ideas about costumes, and they got skimpier, bustier, flashier.

Then the reverse happened; western dancers went to the Middle East to perform, and eventually costume fashions merged.

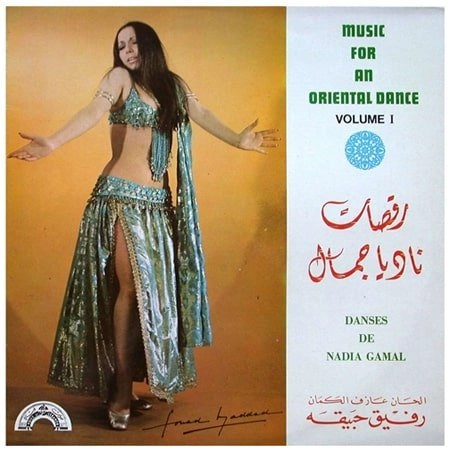

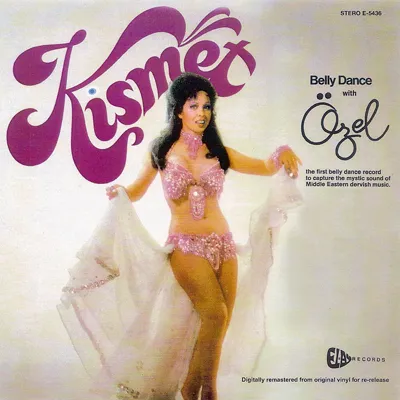

Nadia Gamal and Ozel Turkbas (USA and Turkey) 1980s and Afterwards

It’s fun to look back costumes of the 1980s. Long fringe was in; sometimes more than twelve

inches. Skirts became voluminous again to show off spins and provide modesty for Turkish drops and floor work. Puffy sleeves made a comeback, and the body stocking, once required in Egypt, became a fashion statement in North America. When Egyptian dance star Dina arrived on the scene her influence on costumes was enormous. She has a dance bra named for her; the Dina Bra, and it’s the most popular bra style today.

Dina shocked audiences by wearing mini skirts or shorts. Her athletic body was well suited for these styles. Now it is more common to see a tight skirt than a flowing skirt, bare feet

instead of high heels, and little or no fringe. Everything goes, and costume styles are more international than middle eastern. Everything evolves, and ideally the sharing of cultures has a positive impact.

Costumes themselves are performance art.

A sidenote: I began performing in the late 1970s and have witnessed all the changes/innovations since that time. Costumes influence style, and vice versa.

Here is a picture of me from 1980 during my body stocking phase.

References

Cathy began her Middle Eastern dance training in 1977, studying with several world-renowned Egyptian dance masters, and went on to perform professionally as a soloist for many years. She also trained and performed with various Egyptian and Lebanese folkloric dance troupes in the Ottawa area.

Cathy moved to Lebanon in 1981 and lived there for seven years, exploring the music, dance, culture, and language. After returning to Canada, she resumed teaching and performing. Her first passion is folklore and she is committed to preserving and sharing traditional dance.

Comments